As in years past, trial results offered up a mixed bag of goods and duds at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease Conference, held October 24–27 in Barcelona, Spain. In the first Phase 3 AD trial ever conducted in China, a seaweed oligosaccharide was claimed to have halted or even reversed the slide into dementia of people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s. In a more familiar story, another offbeat approach—a plasma exchange therapy—was reported to slow decline in people with moderate, but not mild, AD. Not so for the fyn kinase inhibitor saracatinib, which hit the end of the road. New Aβ vaccines advanced, and the first clinical trial of an antiviral drug potentially offers a new angle on AD. Finally, the neurosteroid allopregnanolone inched ahead, though estrogen receptor-modulating PhytoSERMs did not.

First, news from the home team. Antonio Páezof the Barcelona-based blood products company Grifols, presented topline data from the Phase 2b/3 AMBAR (Alzheimer’s Management by Albumin Replacement) trial. The14-month regimen of repeated plasma exchange and albumin replacement (PE-A) slowed cognitive decline in people with AD, Páez said.

Most Aβ in the blood is bound up with the protein albumin. AMBAR is a form of plasmapheresis designed to exchange Aβ-laden, oxidized albumin with clean protein. Siphoning off peripheral Aβ should draw Aβ peptides from the brain, the thinking goes, while fresh albumin boosts the blood’s antioxidant, immune-modulatory, and anti-inflammatory capacities (Boada et al., 2014).

Last year at CTAD, Grifols presented data from a pilot study suggesting trends toward improvement in cognition (Dec 2017 conference news). The new trial enrolled 350 volunteers aged 55–85 with mild to moderate AD, and ran at 41 sites in Spain and the U.S. Participants were randomized either to exchange and replacement, or to an elaborate sham procedure that kept patient, caregiver, and clinical raters blinded. After six weekly treatments, the trial switched to monthly sessions for one year. It compared three treatment conditions: two doses of albumin in combination with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and one dose of albumin alone. IVIG contains immunomodulators and human antibodies including anti-Aβ; some preparations had shown promise in AD but failed in later-stage trials (e.g., Gammagard®, Octagam®10%) (May 2013 news). The investigators hoped they might see an added effect of the albumin-IVIG combination on the primary outcomes of change from baseline on the ADAS -Cog and ADCS-ADL after 14 months.

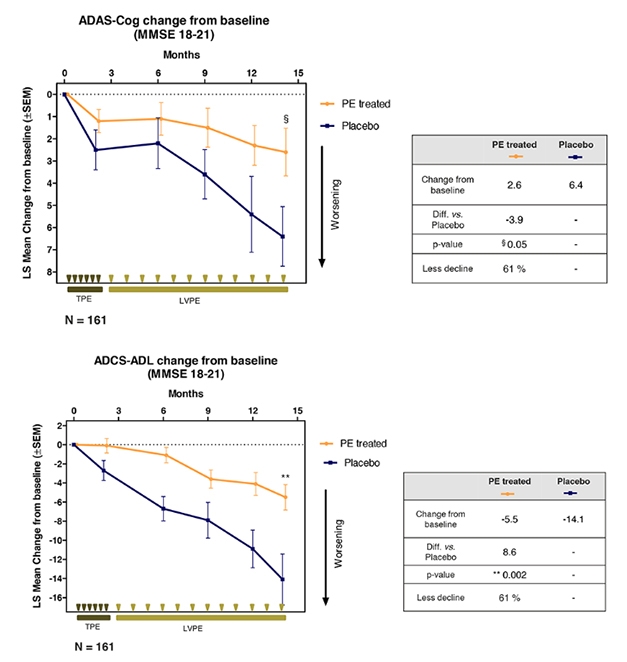

Exchange for the Better? Plasma exchange and albumin replacement slowed worsening in ADAS-Cog (top) and ADCS-ADL (bottom) in people with moderate AD. Participants received six weekly total plasma exchanges (TPE), followed by 12 monthly low-volume plasma exchanges (LVPE) and albumin replacement. [Courtesy of Grifols.]

Alas, it was not to be. While each of the three treatment groups showed between 50 and 75 percent less decline on the ADAS-Cog than placebo, the differences were not statistically significant. When the investigators lumped the three treatment arms into one group, the combined cohort declined 66 percent less than placebo, which just skirted significance (p=0.06). On the ADCS-ADL, the pooled group declined 52 percent less than placebo, which did reach significance, with a p value of 0.03.

A prespecified subgroup analysis split the trial cohort into two equal groups of high versus low MMSE scores. This unmasked a treatment benefit in the latter, Páez said. The mild dementia group, whose scores ranged from 22 to 26, did not decline over the study period, with or without treatment. In the moderate group, with scores between 18 and 21, the placebo group dropped from baseline both on ADAS-Cog and ADCS-ADL, and treatment reduced that decline by 61 percent on both measures. In this analysis, each treatment group had 39 people on placebo and 122 on treatment.

With 4,709 procedures completed, the study was the largest series of plasma exchanges ever dedicated to a single disease, Páez said. Seventy-two percent of volunteers completed the study, and the most frequent complication was local reactions to the catheter. Jeffrey Cummings, Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, praised the investigators for achieving this many plasmapheresis sessions in people with AD with virtually no serious adverse events. “It’s an achievement to bring this fairly intense procedure to bear on patients substantially compromised by AD,” he said.

Researchers debated the lack of decline in the mild group, which was unexpected. The investigators suspect placebo effects, which can be powerful in intervention trials, especially of intensive procedures. Lon Schneider, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, offered another explanation. “This is a potentially compelling set of outcomes, but you’ve a priori split the sample into these mild and moderate groups, and then we start to speculate,” he said. A number of factors could be masking an effect in the mild group, Schneider suggested, including their ADAS-Cog baseline scores, cholinesterase use, and age. “If you had shown these coefficients and baseline scores, we might be having a different discussion,” he said.

What now? Páez said Grifols plans to run at least one new clinical trial, perhaps trying different frequencies of plasma exchange in moderate AD. The company also has other plasma protein fractions to test, he said.

From Blood Products to Gifts From the Sea

Meiyu Geng, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, presented Phase 3 results of GV-971, a seaweed-derived oligosaccharide. In July, its developer, Shanghai Green Valley Pharmaceuticals, claimed that taking this oral drug for 36 weeks improved ADAS-Cog scores in people with mild to moderate AD (press release). Back then, the company announced it would seek approval to market the drug in China this year.

Green Valley bills GV-971, aka oligo-mannurarate, as a jack of all trades. Unpublished preclinical data suggests the compound inhibits Aβ fibril formation, is anti-inflammatory, and even normalizes gut microbiome changes connected to Alzheimer’s disease, Geng told Alzforum. In the trial, 818 participants with clinically diagnosed mild to moderate AD took 900 mg in two capsules, or placebo, twice a day for 36 weeks. ADAS-Cog scores were higher in the treatment versus placebo group at four, 12, 24 and 36 weeks, with a mean difference at 36 weeks of 2.54 points. There was a trend toward improvement on the Clinicians Interview-Based Impression of Change, a secondary outcome, Geng said at CTAD.

Other secondary outcomes did not budge, including ADCS-ADL, the neuropsychiatric inventory, or FDG-PET in a subset of participants. A subgroup analysis revealed the drug had its largest effect on the more severely affected people with MMSE scores between 11 and 15.

The treatment was well-tolerated, with 80 percent of people completing the trial and similar adverse event rates between treatment and placebo groups. The company is planning a global trial of GV-971 to confirm the findings in China, and will add biomarkers to probe the potential mechanism of action, Geng said. According to ClinicalTrials.gov, the investigators are recruiting for a small study in China that will assess safety and pharmacokinetics of higher doses.

Some audience members said that the results reminded them of the trials for first-generation cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine. People in this study were not taking those medications, Geng said. In China, she noted, AD is rarely diagnosed, and thus often untreated. Most people have no access to those drugs.

Vaccines Inch Forward

Two amyloid vaccination strategies are slowly moving along. Ajay Verma, of United Neurosciences in Hauppauge, New York, reported on an Aβ1-14 immunogen. The peptide elicits antibodies that bind Aβ oligomers, fibrils and plaques, but not monomers. The vaccine’s claim to fame is safety. It caused no amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in a Phase 1 trial, and so far hasn’t caused any ARIA through the first half of a Phase 2a trial in people with mild AD (Dec 2017 conference news). That trial, which administered 12 doses over 60 weeks, followed by 18 weeks of observation with periodic PET, MRI, and cognitive tests, is now complete. The data is still blinded, but safety signs continue to be encouraging: 41 of 43 participants completed the study, with no sign of ARIA-E. Verma promised top line results by the end of the year and full data at the AD/PD conference in March in Lisbon, Portugal.

Safety is also looking good for another active, N-terminal Aβ immunotherapy. Bjørn Sperling, H. Lundbeck A/S Valby, Denmark, presented interim data on its ongoing first-in-human Phase 1b study of LuAF25013. Taking place in Sweden, Finland, and Austria, the trial has enrolled 40 of a planned 50 people with mild Alzheimer’s and CSF biomarker-confirmed brain amyloid, who will receive vaccine at four different doses for up to two years. LuAF25013 elicits antibodies to aggregated forms of Aβ, which recognize plaques in brain, Sperling showed at CTAD. As of September, safety looked good, Sperling said, without ARIA-E or other serious adverse events related to treatment. Most events were mild injection-site reactions; none prompted dropouts. Six participants developed at least one new ARIA-H while on the trial; all were asymptomatic. Sperling said Lundbeck will enter Phase 2 in the first half of 2019, vaccinating 200 people with CSF biomarker-confirmed AD. The primary outcome will be change in brain amyloid measured by PET, with secondary measures of cognitive and behavioral impairment plus antibody titers and bio markers of neurodegeneration.

Going Viral?

With recently renewed rumblings about a role for infection in the etiology of some cases of AD (Jun 2018 news; Jun 2018 news), a Swedish company has jumped in with a treatment idea. Nina Lindblom of Apodemus AB in Solna, Sweden, and colleagues at the Karolinska Institute presented results from their trial of an antiviral treatment. They target enterovirus, the most common human pathogenic virus and the cause of 1 billion infections annually just in the U.S.

Thinking that repeated infections might stoke neuroinflammation in adults with AD, the researchers asked if they could slow the rate of AD progression by preventing new infections or treating persistent, low-grade infections. To do that, they use Apovir, a combination of the experimental anti-enterovirus agent pleconaril, originally developed to treat the common cold, and the hepatitis C treatment ribavirin, which was added to prevent the emergence of resistance. In a Phase 2a study, they treated 69 people with mild AD with Apovir or placebo for nine months, then followed them for another 12 months.

During the treatment phase the dropout was high, Lindblom reported. Side effects of ribavirin caused half the treatment group to leave. By nine months, there were but 18 people left in the treated group, and 31 taking placebo. Nonetheless, there were some hopeful hints. The ADAS-Cog worsened steadily in the placebo group over time, but the treated group improved on this measure by three points over baseline at nine months. CDR-SB scores worsened in the placebo but not the treated group. After treatment stopped, both groups progressed at the same rate.

A post-hoc analysis suggested these results were not due to the dropouts, Lindblom claimed. Moreover, change in ADAS-Cog scores correlated with plasma concentrations of pleconaril, suggesting that this drug is more important for the treatment effect than ribavirin.

Lindblom told Alzforum that Apodemus is continuing development with pleconaril alone. A new, Phase 2 trial started in Poland and the Czech Republic in July 2018. Lindblom said it is similar to the previous trial but will evaluate 600 mg/day pleconaril alone versus placebo as an add-on to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or memantine. The trial will initially enroll 120 patients, and use change on ADAS-Cog 11 at one year as primary endpoint. Apodemus expects to perform an interim analysis in the third quarter of 2019.

Going Hormonal?

Roberta Diaz Brinton, Arizona University, Tucson, reported on a completed Phase 1 trial of allopregnanolone, a naturally occurring neurosteroid that stimulates neurogenesis and dampens inflammation and Aβ production in mice. Brinton had previously shown partial results of this small trial (May 2017 conference news). It tested 12 weekly infusions of 2, 4 and 6 mg of allopregnanolone or placebo in 12 women and 12 men with mild cognitive impairment or early AD. The treatment continues to be safe across these doses; Brinton reported no adverse events, no ARIA, and clinical results in the normal range. When they ramped up dosing to find a maximum tolerated dose, women became sleepy at 10 mg, men at 6 mg.

Brinton also spotted some MRI and functional MRI signals associated with allopregnanolone. Compared with placebo, treatment slowed left hippocampal atrophy, and this effect was more pronounced in APOE4 carriers. High-dose treatment improved functional connectivity between the right parietal lobe and posterior cingulate cortex. The 4 mg dose evinced stronger connectivity between the default mode network and the left thalamus or the left putamen compared with placebo. Do these changes translate into better cognition? Brinton is not sure, but called the results encouraging evidence for changes in synaptic function. Exploratory cognitive measures showed high variability and no significant differences between groups, though CogState battery scores did move in the direction of improvement with treatment.

To predict a person’s response to allopregnanolone, Brinton’s team generated induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs) from blood cells of patients in the trial, which they then differentiated into neuronal progenitors and treated with allopregnanolone. At CTAD, Brinton drew a correlation between allopregnanolone induction of mitochondrial respiration in a person’s IPSC-derived neuronal stem cells and his or her change in hippocampal volume. In people whose mitochondria responded to the hormone, the hippocampus atrophied less. With these tools in hand, Brinton has submitted a proposal to the NIA for a Phase 2 study of 200 participants, treated for up to 18 months.

On a less-cheery note, USC’s Schneider presented final results from a Phase 1/2 trial of PhytoSERMs, a plant-based estrogen receptor-beta targeting formulation he and Brinton developed. It zeroes in on brain estrogen receptors while minimizing effects at peripheral alpha receptors (for background, see Dec 2014 conference news).

Schneider and Brinton evaluated whether the supplement would improve symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women with cognitive complaints and hot flashes. They gathered safety, pharmacokinetic, and efficacy data for up to 12 weeks of daily dosing in 71 healthy women age 45–60 who reported at least one cognitive complaint and one vasomotor-related symptom per day, i.e., hot flashes or night sweats.

The PhytoSERMs were safe but failed to improve cognitive symptoms. The vasomotor endpoints suggested a potential for efficacy. Schneider said that if Brinton and he were to take PhytoSERMs forward, it would be as a food supplement focusing on those, not on cognitive symptoms.

The end also came for the fyn kinase inhibitor saracatanib, aka AZD0530. Christopher van Dyck, Yale University, presented data on a negative Phase 2a trial of the compound, originally developed by AstraZeneca to treat cancer. The Yale group worked with the Alzheimer’s Therapy Research Institute at the University of Southern California to repurpose saracatanib for AD, because fyn mediates Aβ synaptotoxicity and tau dysfunction in model systems (Um et al., 2012; Ittner et al., 2010).

The investigators knew from Phase 1 that the drug had a narrow therapeutic index, meaning that pushing the dose to achieve effective brain levels would bump up against toxicity (Nygaard et al., 2015).

Called CONNECT, the current trial tested whether 12 months of saracatinib would slow disease in 159 people with AD. Its design was innovative, using FDG PET as a primary outcome. Alas, the drug did not slow the disintegration of the FDG-Pet signal, or change any of the other outcomes. At the same time, adverse events and the number of people who quit the study showed that dosing was maxed out. “I don’t think this can be pursued at any higher doses than we did,” said van Dyck. While the drug failed, FDG acquitted itself well as an outcome measure, he said. It correlated with clinical measures, and boasted tight confidence intervals, implying it might allow detection of smaller drug effects than the cognitive tests, he believes.—Pat McCaffrey